La scoperta di SCO-X1

THE IDEA: The first attempts failed. In the two years after, Riccardo Giacconi's team at American Science and Engineering in Cambridge, Massachusetts had developed a detector a hundred times more sensitive than any ever flown before. For several hundred seconds on the 18th day of June, 1962, the rocket will sweep the sky, looking at our Moon.

What?! X-rays from the MOON????

Yes, the Moon shines by reflected light of the Sun, so a certain fraction of the Sun's X-rays will be reflected off the lunar surface, back toward the Earth, and the rocket. It was logical to look at the Moon as the next step in exploring the X-ray universe.

THE SURPRISE: One day past full, and 35 degrees above the New Mexico horizon, glittering the desert with its visible light.

Almost immediately, an enormous spike appeared on the chart recorder, as the rocket spun round and round, looking at the Moon and elsewhere in the sky as well. Rather than being jubilant, team member Herb Gursky was initially dismayed.

"Oh, no!" he shouted.

His tone was dejected because he knew that the Moon would NEVER be that bright in X-rays. However, after a few minutes, he realized that the spike that was seen over and over again as the rocket X-ray detectors swept over the sky, was not from the Moon at all, but actually came from another part of the sky, about 25 degrees away! It turned out that the Moon's X-ray brightness contributes virtually nothing to the count rate we see displayed below.

THE DISCOVERY: After several months of analysis back at their laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Giacconi, Gursky, and Frank Paolini reached a surprising, but unmistakable conclusion: the signal was real, not an equipment malfunction, and not from the Moon. It was from a cosmic source of X-rays of truly staggering proportions. From the depths of space, came X-rays so plentiful that they exceeded the Sun's entire energy output by a factor of 100, and exceeded its X-ray output by a factor of about one hundred million!

It was a totally new type of object, dubbed SCO X-1 (for the first X-ray source to be discovered in the constellation of Scorpius).

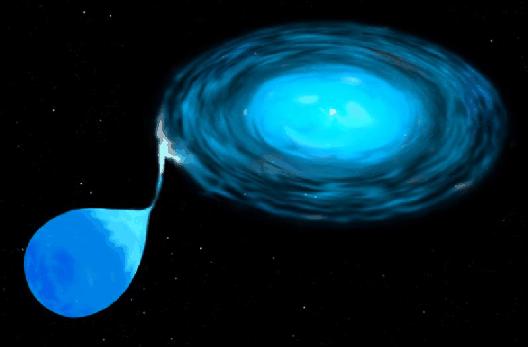

TO INFINITY ... AND BEYOND!: This and subsequent rocket flights soon made it clear that Nature is showering us with X-rays from virtually everywhere. After the discovery, the search was on in the sky to see which "star" was giving off the X-ray light. The answer was not long in coming; a completely obscure but very peculiar blue object in the constellation of Scorpius was the culprit.

On Oct. 15, 1967 Walter Lewin and collaborators at MIT observed SCO X-1 and discovered the first extra-solar X-ray flare ever. So now we found out that these X-ray stars could change their brightness in just a few minutes! Soon rocket flight after rocket flight revealed more of these strange objects, and theoretical astrophysicists realized that neutron stars were responsible for the stupendous energy generated by many of these cosmic X-ray beacons. A whole new field of science had been born, galactic X-ray astronomy.

It was only many years later that scientists found convincing evidence for its binary nature, even though they were quite certain that there must be a companion star.

A scant ten years ago, a strange signal was detected from SCO X-1, (as well as from certain other X-ray sources). Named "quasi-periodic oscillations" (or QPO's), these elusive pulses of X-rays come and go like the wind, lasting a few hundred seconds, only to return and do the same thing again, but slightly differently each time. During these hundred second outbursts, the light comes and goes much like a rotating lighthouse beacon, about once every second. We already know that these phenomena come only from a class of objects called low-mass X-ray binaries, of which SCO X-1 is a member.

P.S. We eventually did discover X-rays reflected from the moon.